From American Society for Aesthetics Newsletter, 2012. Issue 32.1.

Michael Krausz

Michael Krausz is the author of Rightness and Reasons: Interpretation in Cultural Practices; Varieties of Relativism (with Rom Harré); Limits of Rightness; Interpretation and Transformation: Explorations in Art and the Self, and Dialogues on Relativism, Absolutism and Beyond: Four Days in India. Krausz is contributing editor of eleven volumes on such topics as relativism, rationality, interpretation, cultural identity, metaphysics of culture, creativity, interpretation of music, and the philosophy of R.G. Collingwood. Krausz is the former Artistic Director and Conductor of the Great Hall Chamber Orchestra at Bryn Mawr, comprised of forty-six young professional and conservatory musicians. Krausz has mounted thirty-six solo and duo exhibitions in the United States, Great Britain, and India, and has participated in many group exhibitions. He studied art at the Philadelphia College of Art. He is a member of the Artist's Exchange (Delaware), a guild of a dozen professional artists who critique each other's works. In 2009, Delaware by Hand bestowed upon him the distinction of "Master." Krausz is represented by Gallery 50, Rehoboth, Delaware. Recent works may be seen on his website: http://www. krauszart.com.

Krausz says, I have been actively painting for about forty-five years. My paintings depict open meditative spaces, simultaneously displaying multiple spatial planes. Upon color fields, I superimpose inscriptions or ciphers of no literal significance. My works concern the emergence and dissolution of ciphers in infinite spaces. Sometimes the ciphers are small and delicate. Other times they are larger and assertive. Sometimes the marks arise from hand or wrist motions. At other times they arise from elbow and full-arm motions—similar to my gestures used while conducting the Great Hall Chamber Orchestra. While I am right-handed with my baton, I am left-handed with my brush.

With wide horse-hair brushes, I grind powdered pigments into the subtle surfaces of museum board. Then, with thinner brushes, I apply the ciphers. My thinner brushes are made of the hairs of deer, elk, and fox. They have a life of their own. After dipped in water-based pigment, with only slight pressure on museum board, they make very fine, thin lines. With greater pressure, a brush's bulbous base releases a swath of pigment on to the surface. After the ciphers dry, I smear their residue, leaving visible traces of my motion. I characteristically use earth tones: raw umber, burnt umber, burnt sienna, red oxide, as well as graphite and black. Often ciphers are applied with India ink. With a final fixative spray, the colors emerge in unpredictable ways, ever more vibrantly.

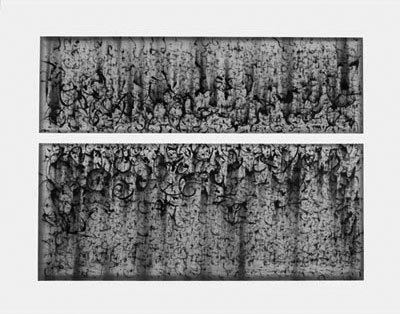

Michael Krausz, After China III, 32x40, mixed media.

Black and white reproduction by permission of the artist.

As I begin, I have a general vision in mind of what the painting will look like when it is completed. Yet I allow the materials their own life. As a work unfolds, the materials suggest their own possibilities. Sometimes unintended results are welcome, sometimes not. I am intrigued by the possibilities of the media. Their sheer materiality is satisfying. As I work on a particular piece, I am aware of its place within a larger body of works. Just as a single work may embody emergent features, so too may a series of related works give rise to emergent directions. These features and directions may become apparent when I view a series as a whole, for example, in a solo exhibition.

I think of my recent artistic path as following one trodden before me by Mark Tobey and Mark Rothko: Tobey, for his extraordinarily evocative linear brush work; Rothko, for his deeply moving color fields. In addition, I have been inspired by Japanese and Chinese calligraphy as well as by the conceptual and spiritual spaces of Buddhism and Hinduism. In earlier times, I was influenced by Ellsworth Kelly's minimalist hard-edged paintings, and by Ben Nicholson, for his contiguous harmonious geometrical reliefs. I have long been inspired by the works of Constance Costigan, for her metaphysical surrealistic "inscapes" that evoke quietly sensual infinite spaces, fashioned with meticulously layered graphite. Others whose work I have particularly admired include Adolph Gottlieb, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, and—still earlier on—minimalists Ad Reinhardt and Agnes Martin.

I never have a title in mind before starting a new work. Rather, I settle upon a title after a painting's completion. Sometimes the title of a piece suggests itself after I have had a chance to live with it a while. Sometimes a viewer will see something in a painting that I myself hadn't seen before. Sometimes a painting's title will suggest itself in relation to other paintings. At other times, a title may be related to the location at which it was made. Sometimes a work will be numbered as part of a series. More importantly, my titles characteristically do not impart assertions of what a work is about. Rather, I offer them as commendations: "Try this way of looking at it! See what happens." I find my way as I make it. I create the spaces in which I wish to dwell. Sometimes, as in After China, III,1 the result is a scene I could not have imagined before starting the work. Sometimes the scene provides a space that invites my vicarious entry.

I had not been particularly visually aware until I was twenty-eight. Then, rather suddenly, painting came upon me. It was then that I visited the studio of noted artist, Leah Rhodes. Upon seeing her large shaped canvases, I had what John Dewey called a "consummatory experience." I suddenly experienced myself in the space of Rhodes's works instead of looking at them. I experienced an "interpenetration" of my self into the space of the painting. Suddenly, I became extremely visually sensitive—to spatial relations, to colors, and more. As a consequence of that experience, I needed to paint. As a matter of "inner necessity," as Wassily Kandinsky would have put it, I had to paint; and paint I did—obsessively! After one year of intense work, I had my first solo exhibition at a local bank. It featured shaped canvases and abstract, minimalist serigraphs. That was the beginning. But what was this originating consummatory experience of selflessness—of non-duality between self and other, between subject and object, between artist and work—where binary oppositions are "dissolved" or "transcended? Arthur Danto helps me here. He describes such non-dualistic experiences as:

high moments . . . of pure creativity, when artist and work are not separated by a gap of any sort, but fuse in such a way that the work seems to bring itself into existence. At such points—and any creative person lives for these—there is none of the struggle and externality that marks those phases of artistic labor in which inspiration fails and the work itself refuses to cooperate . . . which is the state at which . . . so much of Oriental philosophy . . . aims.2

Robert Henri helps as well. Speaking of modern art, he says:

The object . . . is the attainment of a state of being, a state of high functioning . . . whether this activity is with brush, pen, chisel, or tongue, its result is but a by-product of this state, a trace, the footprint of the state . . .[It] is fundamental to creative activity, while skills and measurements are secondary.3

Here is my personal program, as I call it. I understand my creative work to include more than "thingly" products. It includes process as well as product, verb as well as a noun, act as well as outcome, doing as well as what is done. It recognizes nondualistic experiences as benchmarks of my creative life path. It allows for unintended by-products of the mix of media and spontaneous movement.

Several related questions arise here. Should we count a personal program such as mine as relevant for the interpretation of its ensuing products? Does my personal program indicate what my paintings mean? Or does it indicate only what motivated their production? This is not the place for me to elaborate upon such questions. For now, as regards the interpretation of my paintings, I leave that to others.

Endnotes- Number 41 in my website: https://krauszart.com/gallery.html.

- Arthur Danto, Mysticism and Morality, New York: Basic Books, 1972, p. 110–111 Emphasis added.

- Robert Henri, quoted in Chang Chung-yuan, Creativity and Taoism: A Study of Chinese Philosophy, Art and Poetry, New York: Harper Colophon Books, 1970, pp. 203–4. Emphasis added.